Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 55, No.2 - Summer 2009

Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas.

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 55, No.2 - Summer 2009 Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas. |

Sąjūdis’s Peaceful Revolution, Part II

[Continued from previous issue, Vol 55:1]

DARIUS FURMANAVIČIUS

Darius Furmonavičius, PhD, (European Studies, University of Bradford) is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bradford and Director of the Lithuanian Research Centre in Nottingham. He is the author of Lithuania Rejoins Europe (East European Monographs and Columbia University Press, 2009).

ABSTRACT

This article is Part 2 of Darius Furmonavičius’s study about

the

Lithuanian Reform movement Sąjūdis and its successful political

strategy in achieving Lithuania’s independence by peaceful

demonstrations and parliamentary means. The focus is on

Sąjūdis’s

role in affecting the outcome of two crucial elections: the Supreme

Soviet of the USSR and the Supreme Soviet of Lithuania. The

intellectual leadership that presented itself as a reform movement,

implementing Gorbachev’s perestroika, used the mistakes and

misjudgments of the Kremlin leadership to steer the movement away from

Kremlin’s control. Thus, Sąjūdis’s victories led

first to

the dismantling of Soviet power institutions in Lithuania and

eventually the collapse of the Soviet Empire.

As time went on, public environmental demands addressing Soviet authorities assumed a more overtly political dimension. An example of this was the public meeting that took place in Gediminas Square in central Vilnius on July 9, 1988, organized by the Sąjūdis Founding Group. It invited all the Lithuanian delegates to the Nineteenth Conference of the Communist Party in Moscow to attend. When the day came, it was very evident that the First Secretary of the Communist Party Algirdas Brazauskas was troubled by the sight of the Lithuanian national flag flying in this public place and was in a dilemma as to whether or not to address the meeting. His perplexity must have been compounded by the fact that Sąjūdis had passed a special resolution anticipating this occasion, demanding that delegates to the Moscow Conference should express the interests of Lithuania there, rather than simply being puppets of the Kremlin. The leaders of the Communist Party were again obviously wrong-footed about these events, and inevitably they had to turn to their masters in Moscow for advice. It was not until August 18, 1988, following a high-level visit by Alexander Yakovlev, a member of the Moscow Politburo, that the prohibition against flying the national flag and singing the Lithuanian national anthem were withdrawn. In Soviet terms this was a major concession. They could now be used publicly and were indeed granted coexistence alongside the symbols of the communist state. While this was a step toward victory for the Sąjūdis movement, Moscow was deeply concerned about the growing conflict between Sąjūdis and the Communist Party. This concern was behind Yakovlev’s visit. However, his review of the situation produced positive results, because it was announced that Sąjūdis’s existence was legal, on the grounds “that Sąjūdis was not an opposition party” but a movement in support of Gorbachev’s perestroika. It is clear that the Kremlin was hoping to increase Communist Party influence in Sąjūdis and on the course of events in Lithuania. In consequence of his visit and advice, communist officials were ordered not to resist the election of “Sąjūdis communists” to leading positions inside the party, and television coverage of Sąjūdis meetings and events was allowed on the Republic’s TV channel.1

These events marked a significant amelioration. “It was good that it was Yakovlev who came and not somebody who was more narrow-minded,” said Vytautas Landsbergis during an interview for the BBC, and he added:

Yakovlev managed to understand a lot of things in the right way. After all, he was a supporter of the reforms, and of course he had seen the world, and he’s not a narrow-minded party functionary who’s spent all his life in Moscow, and he understood that the changes were necessary and needed. […] From these meetings with Yakovlev the main conclusion was that Sąjūdis is not a bad thing. It should not be abolished. It should not be persecuted. That, at least partially, it was working in the right direction. There was a warning that something bad could come of it, but that there was a need to reasonably develop this movement and for the governing bodies to use this movement to their own purposes.2

While these observations reflect the truth of the situation, it is also evident, with hindsight, that the Kremlin’s strategists had seriously underestimated the role of Sąjūdis and its influence on the Lithuanian population. Soon after Yakovlev’s visit, Sąjūdis’s largest event was organized when the Founding Group planned another public rally under the title Istorinė teisingumo diena (Historic Day of Justice). This gathering, which will be described in more detail below, can be considered to be the most crucial turning point in Sąjūdis’s history. Indeed, it has been said that the nation became unified in its march to national independence during this very meeting, for the participants included not just the leaders of Sąjūdis but also some Lithuanian members of the Soviet communist elite. The presence and the support of those members, who were tending to favor Sąjūdis, were becoming increasingly important. The event was to be held in Vingis Park, Vilnius, on August 23, 1988, and was advertised as an occasion to mark the forty-ninth anniversary of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Nearly 150,000 people participated. The occasion was presided over by the Chairman of the Sąjūdis Founding Group, Vytautas Landsbergis, and many other members of the Founding Group, together with many prominent intellectuals and some members of local Communist Party elite, participated in the gathering. The live transmission of the events by Lithuanian TV also rallied the entire nation behind the quest for independence that emerged from the gathering.

The true significance of the Vingis Park Rally was the fact that the whole truth about the secret division of Europe between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany was expressed there in public for the first time since the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in 1944. In his speech, Vytautas Landsbergis explained how Lithuania had become the victim of two criminal regimes, Stalinism and Nazism. He called everybody’s attention to the fact that the attempted commemoration of the anniversary of the pact one year earlier had been disbanded by the Soviet authorities on the grounds that it “constituted an anti-Soviet activity.”3 This action was, in itself, a candid exposure of the way in which the communist system had conspired to hide the truth. It was an observation that served to reinforce the impact of the poet Justinas Marcinkevičius’s contribution to the debate, in which he called loudly for the open publication of the secret documents of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. These documents, he said, had been hidden from the public for half a century. He also condemned the pact, not just for its secrecy, but for its brutal violation of international law and for the fact that it had led to the outbreak of the war. He then demanded the opening of all Soviet archives to scientists, historians, journalists and anyone else interested in history in order to set the record straight, so that a new and honest school textbook of Lithuanian history could be published that was free of Soviet falsification.4 When he had finished speaking, another academician, Antanas Buračas, spoke about the need to restore the flag of independent Lithuania.5 Lionginas Šepetys, Secretary of the Central Committee of Soviet Lithuania’s Communist Party, then said that if the Soviet News Agency TASS continued to spread disinformation claiming that Sąjūdis had no popular support, he would be the first to deny such claims.6 He was followed by Edmundas Atkočiūnas, a priest, who mentioned that Father Alfonsas Svarinskas and Father Sigitas Tamkevičius, as well as Petras Gražulis, were still held in Russian gulags as political prisoners, despite perestroika.7 Next the historian Gediminas Rudis spoke about the direct consequences of the deal “between the two most reactionary and brutal dictatorships of the twentieth century,” explaining in particular just how Lithuania’s occupation by the Soviet Union had been a product of this pact.8 Finally, the philosopher Arvydas Juozaitis expressed the wish that there would be no more falsifications of Lithuania’s history, whether in academic research or in the press.9

Vytautas Landsbergis invited the audience to listen to the testimony of Juozas Urbšys, who had been independent Lithuania’s last Foreign Minister between 1938 and 1940. He had recorded a speech especially for this rally from his flat in Kaunas. Juozas Urbšys’s message announced that “during Lithuanian – Soviet negotiations in Moscow about the transfer of Vilnius to Lithuania in October 1939, Stalin had openly admitted that the USSR had made a deal with Germany, yes, the same fascist Germany, that the largest part of Lithuania should belong to the Soviet Union and a narrow strip along its borders to Germany. He had laid a map of Lithuania on the table and showed the division line drawn on the territory of independent Lithuania, separating the possessions of Germany from those of the USSR.”10 Urbšys added: “I tried to protest against such a partition of an independent state, saying that Lithuania could never have expected that from a friendly USSR.”11 Doubt as to whether the agreement of 1939 had ever really served the best interests of the Soviet Union, as Soviet historians claimed, were then voiced by the historian Liudas Truska. He pointed out the heavy cost of the pact to the Baltic States and Poland, arguing that Stalin had been engaged in an attempt to secure the return of the lands that had belonged to the Russian Empire until the First World War, and had therefore pursued a carefully crafted scenario for the reoccupation of Lithuania. In doing this, Truska also mentioned that when Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius, briefly Prime Minister of Lithuania, had arrived in Moscow in 1939, Molotov had openly said that Russia would “use any opportunity to get back to the Baltic Sea” and that “all small states would disappear in the future.”12

It was now the turn of Vladislovas Mikučiauskas, Soviet Lithuanian Foreign Minister, to speak, and he too urged the necessity of condemning the crimes of Stalinism. However, he then moved at once to praise the achievements of Soviet Lithuania. At this, the crowd began to repudiate his message and was unwilling to listen any more.13 The poet Sigitas Geda then took the stage. He discussed the meaning of Lithuania’s annexation and the need to inform “the more powerful nations of Europe and Asia” about Lithuania’s hopes and intentions. His meaning was quite unmistakable, as the term “more powerful nations of Asia” in Lithuanian idiom is a reference to Russia. He added: “There will be no twenty-first century without reconciliation amongst nations.” It was clear to all that he was stressing the necessity of respecting the right of all nations to self-determination. “Lithuania has awakened, has risen, and will rise again,” he declared. It was a bold announcement of faith and hope in the restoration of an independent Lithuania and was perceived as such by the applauding crowd.14 Mentioning efforts currently being made by Lithuania’s authorities to help Artūras Sakalauskas, a Lithuanian soldier in the Soviet army who had been crippled by the criminally brutal treatment he had received, Landsbergis then asked the composer Julius Juzeliūnas, Chairman of the Commission for the Investigation of Stalinist crimes in Lithuania, to speak.15 Juzeliūnas then testified that more than 300,000 people had been deported from Lithuania during the Stalinist terror of the 1940s. He then described the social achievements of independent Lithuania during the twenty years of freedom before the occupation of 1940, describing them as amounting to a miracle. Citing Antanas Sniečkus, the First Secretary of the Lithuanian Communist Party, he pointed to the paradoxical fact that the communists imprisoned by the authorities in Lithuania had been saved from death under Stalin’s terror in Moscow, and appealed that reports made to the Commission in the future should provide details about the victims as well as the perpetrators of Stalinist crimes. This material, he said, now needed to be published openly to make sure that such events would not be repeated in the future. He insisted that people should stop being afraid of breaking promises made to their oppressors under duress to keep quiet about what they had seen in the Soviet prisons and concentration camps. He ended his speech with an appeal:

On this, the eve of the forty-ninth anniversary of the amoral deal between the world’s two most brutal criminals, Stalin and Hitler, we invite the people of Lithuania, calling the whole Lithuanian nation to attention by appealing to the sound of the Varpas (Bell) of Vincas Kudirka, who had spoken for the nation’s freedom a century ago with the cry: “Arise! Arise! Arise!”16

At this, tens of thousands of people lit candles in memory of the victims of Stalinist and Nazi crimes, holding them up in silent protest and in hope.17

The subsequent speaker was the writer Kazys Saja, who announced the names of Balys Gajauskas, Viktoras Petkus, Father Sigitas Tamkevičius, Gintautas Iešmantas and many others, who were still in jail for holding views similar to those expressed publicly in the present meeting. The only “crime” of these prisoners, he said, was that they had been brave enough to give this news openly at an earlier date. He then demanded freedom for all political prisoners currently held throughout the whole Soviet Union, and the crowd responded with exultant shouts of: “Freedom for prisoners of conscience!”18 This cry provided a signal for this momentous gathering to end with an invitation to sing the previously banned National Anthem, while the equally forbidden National Flags and State emblems of independent Lithuania were waved before the crowd. Sąjūdis then announced its demands for the complete publication of the secret protocols of the Soviet-Nazi pact; for the opening of secret and hidden archives; for the rewriting of history textbooks; and for the restoration of Lithuania’s independence. As Vytautas Vardys has put it: “By making all the demands that it did, Sąjūdis placed itself squarely in the tradition of the dissidents who had demanded both Soviet and German denunciation of this pact as early as 1979.”19

In less than three months, “priorities had shifted from the needs of perestroika, as defined by Moscow, to the requirements of political reform as perceived by the Lithuanians.”20 Events were moving at an unexpected pace, but the enthusiasm that had developed had yet to be put to the test.

|

|

Baltic

Way, August 23, 1989.

Approximately

two million people joining their hands to form 600-kilometer-long human chain accross the three Baltic states. Photo

Virgilijus

Usinavičius

|

The growing impatience for national independence that was manifest in Lithuania from the time of the Vingis Park Rally was paralleled in the other Baltic countries, where the Latvian and Estonian Popular Fronts had similarly affirmed their commitment to a peaceful parliamentary route for the restoration of national independence.21 However, neither the formulation of constitutional propositions, nor the preparation of political platforms, nor yet the creation of a popular mood, would be sufficient to move the monolithic impediments to national freedom that the Soviet Union and its constitution, its totalitarian apparatus, its Communist Party, its censored press and media system, and exploitative command economy presented to the would-be reformers. To bring about, then win, free elections in order to liberate Lithuania from Soviet occupation would be merely a first step for Sąjūdis. Indeed, in the event, two important sets of general elections needed to be won at different levels of Soviet constitutional practice just to reach that point. The first of these to be faced was the general election to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union; the second, the general election to the Supreme Soviet of occupied Lithuania, the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic, as it was called in Soviet terminology. The three important dates that mark our description of the progress of these events were first, the declaration of moral independence for Lithuania on February 16, 1989; second, “The Baltic Way,” the largest freedom demonstration the world had yet seen as the peoples of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia linked their hands along the highway running from Tallinn through Riga to Vilnius in a huge protest gathering against the continuing consequences of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop pact on August 23, 1989; and, finally, the celebration of Lithuania’s Independence Day on February 16, 1990. These all proved to be occasions that mobilized support for Sąjūdis both in Lithuania and in the West.22

We have already seen that the initial tactics of Lietuvos persitvarkymo Sąjūdis (the Lithuanian Restructuring Movement), were two-fold, in keeping with its title.23 First of all, the movement declared its support for Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika and glasnost and demanded the full introduction of these purported new realities into Soviet Lithuania. Second, Sąjūdis set out to act as a de facto movement for the liberation of Lithuania from Soviet occupation. In Soviet constitutional terminology, the movement could therefore be described as an expression of the legitimate right of a republic to leave the Soviet Union, while from an international perspective, it was a legitimate movement for national self-determination, a principle protected and guaranteed by the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Third, it was a movement for the restoration of independent Lithuania, which still existed internationally as a legal entity. Finally, Sąjūdis existed as a protest movement to demand Soviet withdrawal from Lithuania, which emphasized the fact that Lithuania and the other Baltic States had been illegally occupied by the Soviet Union.

Within less than five months from the first meeting of the Sąjūdis Founding Group, the movement had fully developed its structure, becoming an active, well-organized and effective political body, with its major goal clearly defined as the restoration of Lithuanian independence. Thus, it emerged rapidly on the political scene of occupied Lithuania as a highly motivated political institution and was soon to suggest alternative candidates for the general elections to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union and to the Supreme Soviet in occupied Lithuania. Sąjūdis candidates were fielded at both levels, focusing their campaign unequivocally on the goal of future independence for Lithuania. The official Communist Party candidates in these contests still viewed the country’s future as remaining within the changing Soviet Union and, therefore, they were cast as the opponents of this policy.

Initially, the Sąjūdis organization had no formal membership requirements. Anyone could join a local Sąjūdis group and could show support for Lithuania’s independence simply by performing voluntary work. The movement’s structure was simple: Sąjūdis’s followers elected representatives to district meetings, and these in turn elected Sąjūdis councils in the cities and regions, although only after full consultation among the different representative groups. Sąjūdžio Taryba, the Sąjūdis Council, was elected, as we have seen, during a general founding meeting, and later Sąjūdžio Seimas, the Sąjūdis Parliament, was elected during the annual general meetings. Many members of this council and this parliament later became the movement’s candidates in elections, both for the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union and for the Supreme Soviet in occupied Lithuania. When they were elected to the Kremlin’s Supreme Soviet in March 1989, with a great majority in most instances, Sąjūdis became the winning and dominant political force in the first free election in the history of the Soviet Union. This was achieved despite the threatening and ubiquitous presence of the KGB, the Red Army, the Soviet militia, and the Communist Party, all institutions of Soviet totalitarian power.

The major initial tactic employed by Sąjūdis was to exploit the Kremlin’s mistakes. It is ironic to suggest that the biggest of these was that body’s acceptance of Sąjūdis as “the Lithuanian Perestroika Movement.” An examination of the events will confirm that the Kremlin had no choice other than to promote perestroika in occupied Lithuania if it was not to lose credibility in the eyes of reformers everywhere. It is also fair to observe that the Sąjūdis movement was sometimes given more space than might be expected by its opponents, even though the objectives of the two sides were radically different. An example of this was the outcome of the visit of Aleksandr Yakovlev, a member of the Politburo of the All-Union Communist Party and the chief ideologist of perestroika in the Soviet Union, who arrived in Lithuania on August 11-14, 1988. This visit was a turning point in Sąjūdis’s relationship with the party. Indeed, Romualdas Ozolas, a member of the Founding Group of Sąjūdis and later deputy Prime Minister of Lithuania, even said after he had left that “we are still alive due to the visit of Alexander Yakovlev.”24 Yakovlev had delivered a lengthy speech to the Lithuanian communists in May 1988 entitled “In the Interests of the Country and Every Nationality,” part of which was shown on republican television, in which he examined many of the problems of Soviet society from “economic stagnation” to “bureaucratism.” It is interesting at this distance in time to note that this appraisal included references to Lenin’s attitude toward “national consciousness,” which, he said, allowed that “ethnic and nation-state differences […] would […] remain for an indefinitely long time after the victory of socialism on a worldwide scale.”25

This visit had rather unexpectedly eased pressure on the Sąjūdis leaders at a critical stage and had given them both the freedom and the time to match their actions more effectively to a speedily changing situation. Alexander Yakovlev has since remembered his meetings with the Lithuanian leaders in the following way:

The reasons why there weren’t any difficulties with them then was that the questions we discussed then were not about independence, or the split of the Party. We talked about sovereignty, economic independence […] If we had acted in time, if we had introduced the principle of confederation then, we would not have these problems now. But our machine, the dictates of its central apparatus that did not take the national interests into consideration, created the problem.26

When asked: “Did you try to persuade the Central C, the Politburo, to change its attitude? Did you encounter resistance?” Yakovlev answered: “It never stopped. The Empire mentality is very well developed.”27 He explained that Gorbachev had also understood the situation perfectly well, but “he had to take the level of understanding in the country into account.”28 He added ironically: “Do you think General Makashov is the only one who thinks that we left Eastern Europe without a fight?”29

Richard Krickus has described how Yakovlev accepted an observation from the Soviet Lithuanian writer Vytautas Petkevičius at one of the public hearings in which he attempted to sound out his feelings. He said: “Isn’t it paradoxical? I know three ethnic languages and I’m being called a nationalist. The person who calls me this knows only one language, Russian. Although he has lived in this republic for several decades, he calls himself an internationalist!”30 Interestingly, this exchange was cut from the program that reported the meeting on republican television. However, the remark, which was in fact directed at the Russian Nikolai Mitkin, the Second Secretary of the Communist Party and the Kremlin’s chief watchdog in occupied Lithuania, was widely publicized in other ways. It reflected a shift in opinion that Yakovlev recognized, and one of the major outcomes of his visit was also the replacement of the rigid and reactionary First Secretary of the Communist Party Rimgaudas Songaila by the more flexible Algirdas Brazauskas. The Second Secretary was also changed and Vladimiras Beriozovas, a Lithuanian-born Russian, was given the post. It was clear from these moves that the Kremlin hoped that Yakovlev’s visit would enable it to better control Sąjūdis, which had undoubtedly remained a target of the Soviet secret security forces.

Now, as a result of his appearance, it temporarily seemed that Sąjūdis was supported, even legitimized, by the Kremlin. For a short period, Moscow actually encouraged communist membership in Sąjūdis, in the hope that its contribution would improve the situation in the republic. Moscow clearly hoped by this device to divert the energy of the population towards the belief that managed change for the Soviet system in Lithuania would be a better alternative than the unpredictable process of pushing for independence. However, the reality proved to be different. Contrary to the Kremlin’s expectations, the Sąjūdis movement managed to win some influence within the Communist Party in Lithuania itself, a process that eventually enabled its separation from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Although a small part of the party remained faithful to its Moscow masters when this happened, the greater part of the membership of the Communist Party in occupied Lithuania was effectively already in a state of schism from the CPSU before the end of 1989. Though the Lithuanian Communist Party senior members were “not prepared to follow Landsbergis wherever he wished to go” and were sometimes subject to a severe strain in their loyalties, the fact remains that they were unwilling from this stage onward to offer active resistance to the expressed will of the Lithuanian people. Nevertheless, despite this improvement, they remained an ambiguous force, especially after Sąjūdis had formed the national government and was facing great international pressure and eventually a full economic blockade.

Three major stages of Sąjūdis’s activity can be identified as it took its planned peaceful and parliamentary route towards the achievement of independence. Initially, as we have already seen, Sąjūdis presented itself as a movement on behalf of perestroika. Its real goals and aims at that stage were implicit rather than explicit, but they could be seen in its symbols or “read between the lines of its text.” Its mode reflected the style of literature written during the Soviet period. The reasons for this subterfuge were prudential, as was the perception that it was necessary to increase political demands on the Soviet authorities gradually. There was also the need to achieve legitimacy in order to avoid the movement being treated as anti-Soviet and thus being disbanded while in its early stages, just as a written text had to satisfy the Soviet censorship before it was published. For these reasons, Sąjūdis used the Soviet lexicon rather widely while conducting its activity within the borders or, in fact, on the edge of what was legal within the Soviet framework. Even Landsbergis, the leader of Sąjūdis’s Founding Group, used phrases like “Soviet Lithuania” at the beginning of his speeches, although he always finished them with the expression “Lithuania.” Gorbachev’s portraits were also carried in public demonstrations in support of perestroika and glasnost, and leading members of occupied Lithuania’s ruling bodies were invited to participate and talk at Sąjūdis meetings. Meanwhile, Sąjūdis policy was essentially one of “push and wait.” During a trip to the United States in June 1989, its leader, Vytautas Landsbergis, stated that “our way is incremental – you push, and you wait and see. This policy was a conscious one. In order to become independent, we started passing laws and pulled away step by step. The Baltic States are in a special category of trying to decolonize gradually.”31

History has since confirmed how the Baltic States continued to make clear their claim of a nonviolent path for liberation from Soviet occupation with a steady and cumulative determination. The three most important factors in persuading the Kremlin to view Sąjūdis as an organization of managed change rather than the liberation movement that it really was were: the acceptance of communists into membership of Sąjūdis; the flexibility of Landsbergis’s leadership in the Founding Group; and the continuing dialogue between the movement and the Soviet authorities. Thus, it had every appearance of acceptability. Organizing the public meeting with the delegates attending the Nineteenth Communist Party Conference before their trip to Moscow was one such deception, done to display commitment to perestroika and change within the Soviet system, but at the same time to seek public assurances from the delegates that they would commit themselves to Lithuanian interests.

It was in this context that the demand for the resignation of Songaila, the First Secretary of the Communist Party in occupied Lithuania, was voiced by Professor Bronius Genzelis, a member of the Founding Group of Sąjūdis and a prominent member of the Lithuanian Communist Party, being its leader at the University of Vilnius. We have seen how Sąjūdis’s position changed following the Vingis Park gathering. Sąjūdis had seized an opportunity. It openly stressed the illegality of the incorporation of the Baltic States into the USSR. It denounced, on the basis of incontrovertible evidence, the international crime committed by two dictators, Stalin and Hitler. Sąjūdis’s position now was that justice had to be restored and that the means of implementation would be the withdrawal of the Soviet Union from Lithuania and the other Baltic States as soon as possible.

The second stage of Sąjūdis’s activity involved the electoral effort to win a majority of the seats allocated to the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Though there had been some changes in the Soviet system since Brezhnev’s days, it would be a mistake to suggest that these elections resembled the electoral process of a democratic society in any way. Within occupied Lithuania, the Communist Party showed great reluctance to implement any changes in the nomination of candidates for the electoral lists. It was Sąjūdis that forced its hand in ensuring that Sąjūdis candidates were able to stand against its lists. It was the first-ever election in the Soviet Union to allow any element of opposition politics. The Kremlin clearly overestimated its ability to control the outcome of the election, e.g., the counting of ballots in its own favor, achieving 99 percent of the “yes” votes, as it used to in the past. One could perhaps argue that holding of general elections in the USSR in a more or less democratic way was a mistake by the Kremlin, at least in the sense that the demonstration of the beginnings of the democratic process were perceived by the Kremlin as being an adequate response to what the country desired. Lithuania wanted democracy, but the nation had reached the point where this demand and that of national self-determination were inseparable in the public mind. Thus, the election offered an opportunity that was exploited effectively by Sąjūdis. It opened the parliamentary way to freedom and the movement succeeded in winning a majority of seats. Lietuvos Laisvės Lyga (The Lithuanian Freedom League), a more radical organization than Sąjūdis, had initially suggested a boycott of the election to the USSR Supreme Soviet on the grounds that such elections might legitimize Soviet rule in occupied Lithuania. Sąjūdis had disagreed, perceiving these elections precisely as a means to steer occupied Lithuania away from Soviet control. Sąjūdis’s leadership, in effect, opted to use the opportunities that the Soviet system offered for its own dismantling. Indeed, since politics is the art of the possible, that was probably the only realistic way under prevailing conditions to achieve the goal of Lithuania’s independence from the Soviet Union.

The beginning of 1989 was marked by a major demonstration calling for the withdrawal of the Red Army that was initiated by the Lithuanian Freedom League. To mark Independence Day on February 16, the Lithuanian Freedom Monument in Kaunas, which had been destroyed by the Stalinist Soviet authorities on Lithuania’s incorporation into the Soviet Union, was publicly restored. In anticipation of the occasion, Sąjūdžio Seimas, the Sąjūdis Parliament, issued its most radical statement to date, calling unequivocally for the reestablishment of an independent, democratic and neutral Lithuanian state. From that moment onward, the declaration “Independence – for a Reborn Lithuania, democracy – for an Independent Lithuania, a decent life – for a Democratic Lithuania!” became Sąjūdis’s main slogan for its election campaign.

The reaction by Moscow and the local Communist Party in occupied Lithuania to these developments was particularly angry. There were ominous rumblings on Moscow radio when Kriuchkov, the KGB boss, claimed that a “fascist dictatorship” was taking power in Lithuania. Locally, the First Secretary of the Communist Party, Algirdas Brazauskas, threatened to tighten restrictions on the increasingly independent press as well as to clamp down on Communist Party members, activities and participation in the leadership of Sąjūdis. The broadcasting of Sąjūdis’s ninety-minute weekly television program was then summarily suspended, and communist officials began furiously denouncing Sąjūdis’s support for political independence, accusing it of deviating from its original intention to support perestroika. Despite these developments and perhaps helped by them, Sąjūdis won 36 of the 41 seats allocated to the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in the election to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union on March 26, 1989. It was obvious that this victory was a clear manifestation of the Lithuanian people’s support for national independence and their wish to put an end to communist ideology and Soviet colonialism. Then, to drive the message home to those who controlled the Soviet system, the new Sąjūdis deputies disseminated a book, which had been printed in Vilnius in the Russian language, with documentary evidence of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. When they arrived at the Kremlin, some 100,000 copies of the book were distributed in Moscow and elsewhere in Russia. They were effectively posting a public notice that the Soviet occupation of Lithuania was based on a fundamentally illegal and criminal treaty.

Sąjūdis perceived the general election to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union as providing an opportunity for the election of representatives of occupied Lithuania to negotiate with the Kremlin on the restoration of an independent state. The representatives it sent to Moscow in 1989 were supporters of Lithuania’s independence, a fact that marked the election as standing in stark contrast with the events of 1940, when Moscow had manipulated a general election in Lithuania unscrupulously in order to have its own representatives nominated to a hastily renamed Parliament, the “Supreme Soviet of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic,” which then arbitrarily announced that it was “the will of the nation” to join the Soviet Union. However, we must note that in 1989 Sąjūdis itself had also not been above some manipulation in the national interest. The former communist leader Algirdas Brazauskas owed his election to the fact that the Sąjūdis leadership regarded him as being potentially useful in the forthcoming negotiation with Moscow. Sąjūdis had withdrawn its own candidate so he could run unopposed. However, the situation was changing, even in Moscow, in a favorable way, and because of this, the Lithuanian and other Baltic delegations were able to persuade the USSR Supreme Soviet to set up a commission to investigate the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocols. Once nominated, this commission set to work quickly, and on August 22, 1989, fourteen of its twenty-six members reported their conviction that the pact should be annulled. Responding to pressure from the Baltic republics, they declared that relations between the Baltic States and the Soviet Union should be governed not by the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, but by earlier treaties, signed by Lenin in 1920, under which the Soviet Union had guaranteed the independence and territorial integrity of all three states. It was very soon after this report was made that Sąjūdis and its allies in neighboring countries arranged the huge (Baltic Way) demonstration in which over a million Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians accepted the invitation to join hands peacefully along a 650 km route, connecting the capitals of the three Baltic States, Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn. This was, of course, a graphic expression of the rejection by the people of these nations of the evil deal that had robbed their countries of both the right to existence and independence, as well as all normal democratic rights, for over half a century, despite the persistent Soviet propaganda that they had joined the USSR freely.

The Baltic representatives in the Kremlin’s Supreme Soviet, including Sąjūdis members, made the most of the initiative now created. They stated that this demonstration was in effect the first referendum in the occupied Baltic states, its scale demonstrating the manifest wish of the Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians to restore their states, and to be independent from the Soviet Union. Naturally, this impressive demonstration was reported on major television news programs across the world, and even within the Soviet Union, despite a campaign of disinformation by TASS. Thus it served the intention of its organizers well. It ensured that full Western attention was drawn towards the illegality of the secret pact and the need to annul its consequences, ending the Soviet occupation of the Baltic States. The climate of international public opinion was beginning to flow in the direction desired by the three Baltic countries.

Despite Moscow’s fury at these developments, the regime refrained from the use of military force. It did, however, attempt to provoke violence by movements of Soviet troops. For example, many more than the normal quota of Soviet soldiers were seen in the streets of Kaunas and, although they avoided causing provocation, troops in civilian dress and KGB officers holding weapons were sent to Sąjūdis meetings. They were often identified by Sąjūdis’s volunteer stewards or by members of the movement’s developing information and intelligence agency, Sąjūdžio Informacinė Agentūra. Naturally, they were often asked to leave as soon as possible. Invariably, these people were alarmed by the presence of television or other cameras and would often disappear soon after being noticed. Moscow also sent troops dressed in civilian clothes to increase support for the communists by voting in the USSR Supreme Soviet election in some constituencies. However, this campaign ended almost as soon as it started because Lithuanian television played with the situation by filming these men, all in identical civilian clothes, with short haircuts, arriving to vote in military trucks. The radio networks also commented extensively on this and other similar attempts at fraud. This tactic of ironic exposure was used a great deal and was a valuable weapon against the war of lies waged by the Kremlin’s propaganda machine. Of course, the fact that its work had backfired became strikingly obvious with Sąjūdis’s victory in the general election. This event briefly shifted the major scene of political events from Vilnius to Moscow, where the deputies of occupied Lithuania were widely regarded as “poisoned tomatoes,” who had come spreading ideas of democracy in the Kremlin. These “separatists,” who had became deputies of the supreme legislative body of the Soviet Union, were now well placed to begin what was perhaps the greatest manipulation of the Soviet system since its establishment in 1917 – the destruction of the Soviet system from the top.

At this stage, Sąjūdis began work to encourage the local Supreme Soviet in occupied Lithuania to proclaim the superiority of the republic’s laws over the Soviet ones, to establish Lithuanian citizenship as a status distinct from Soviet citizenship, and to guarantee these Lithuanian citizens the benefits of the rights which are defined by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.32 Thus, the Sąjūdis deputies in the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union began to act decisively at the local level, using their authority to encourage the Supreme Soviet in the occupied country to prepare laws that would smooth the restitution of the Lithuanian state. This campaign had, of course, begun with particular reference to the upcoming election to the Supreme Soviet in occupied Lithuania, expected to take place on February 24, 1990.33 Underlying this political strategy, Sąjūdis activists were well aware that the economic stranglehold of the command Soviet economy would have to be broken if political separation was to become in any way feasible. A few months earlier, Baltic economic experts had worked out a model for economic independence, and the key provisions of this so-called “Baltic Model” included demands that economic reforms must be based on the principles of a market economy. This implied that the Baltic economies must be firmly under the control of their own governments, and that their natural resources must come under the control of the republics and not belong to the Kremlin. It also required that the occupied Baltic republics must become distinct entities, even within the Soviet Union’s budget, with powers to raise their own taxes.34

During the last months of 1988, occupied Estonia began to move more rapidly along this path toward self-determination than the other occupied Baltic States. On November 17, the Supreme Soviet in Estonia confirmed these economic principles and declared the superiority of the republic’s legislation over Soviet laws. At this stage, the reform process was moving more slowly in Lithuania, where the local Supreme Soviet refused to implement parallel legislation, despite great pressure from Sąjūdis to do so. These matters were tabled for debate. Algirdas Brazauskas, the new First Secretary of the Communist Party, was recalled urgently to Moscow to meet Gorbachev. On his return to Vilnius, he delivered an apologetic speech in a television appearance, in which he gave excuses for failing to lead the republic on a path similar to that taken by Estonia. It was clear that he had accepted Moscow’s orders rather than attempting to resist them. His weakness was fully exposed a few days later, when Sąjūdis declared on November 20, 1988, that henceforth only those laws should be honored that do not limit Lithuania’s independence. This announcement increased the conflict with the Communist Party because Sąjūdis had also declared the moral independence of Lithuania on the same day. Although it did not yet have the power to pass the necessary legislation, the movement had now shown an initiative that it clearly intended to use to the fullest. Within a week, it had gathered signatures from almost half of the entire population of Lithuania to mark its protest against changes in the Soviet constitution, which had been proposed to centralize power in Moscow even further. The prepared constitutional amendments seemed explicitly designed to prevent the separation of the Baltic republics from the Soviet Union. A petition with 1.8 million signatures was presented to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union on November 24, 1988.

The similarity of the political processes in occupied Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia encouraged unanimity and increased cooperation between the independence movements. The representatives of the Lithuanian Sąjūdis and of the Latvian and Estonian Popular Fronts maintained a close liaison, affirming their belief in the peaceful, parliamentary way for the restoration of national independence. The joint meeting of the representatives of all three national movements in Tallinn on May 13-14, 1989 formed the Baltic Assembly, a joint representative and coordinative body of the three liberation movements. It passed the Declaration of Rights of the Baltic Nations, which announced the right of each of the three peoples to live in its historically defined territory; the right to self-determination; and the right of each of the Baltic nations to define its own political status freely. The declaration also emphasized the right of independent collaboration with other states and nations and expressed the collective will to regain state sovereignty in a neutral and demilitarized Baltic and Scandinavian region.35 Having passed this important declaration, the Baltic Assembly also sent letters to the heads of the member states of the Conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe; the Secretary General of the United Nations; and the Chairman of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet, which emphasized that Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian independent states existed with all the privileges of international recognition between 1918 and 1940. They referred explicitly to the criminal secret deal between Stalin and Hitler that had divided Europe into zones of Soviet and Nazi influence and had led directly to the destruction of the independence of the Baltic States and expressed a formal confidence that the Soviet Union would condemn the policy it pursued towards the Baltic States between 1939 to 1940 and would therefore declare the agreements contained in those secret protocols to be invalid. They further expressed the hope that the Soviet Union would no longer impede the negotiation process of the restoration of state sovereignty to Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. The formulation also stressed that the nations wished to reestablish their independence within a neutral and demilitarized zone of Europe. They then passed a “Resolution on Stalinist crimes,” which demanded that the international community should acknowledge that the Soviet policies toward the Baltic States and the Stalinist terror, which accompanied their incorporation into the Soviet system, had been acts of genocide and crimes against humanity. The resolution demanded that the initiators and executors of the communist crimes then committed should be uncovered; that the communist institutions involved should be recognized as criminal organizations; and that an international legal mechanism should be established on the Nuremberg model to investigate those crimes against humanity, as it had dealt with Nazi crimes in the past.

At around this time Maati Hint, a representative of the Estonian Popular Front, delivered a lecture in Tallinn entitled “The Baltic Way” in which he briefly reviewed the relationship between the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian nations, which had lived near the Baltic Sea in a common destiny for thousands of years, at the crossroads of northern and eastern Europe. He spoke of how the foundations for independence laid down between 1920 and 1940 had been cruelly undermined by the totalitarian regimes of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. Despite their having been allocated to the sphere of the Stalinist aggressor under the secret protocols of August 23 and September 28, 1939, and the terror, mass deportations, and forced migration which followed, they had remained faithful to their languages, culture, and national and religious traditions. He claimed: “The Baltic Way is the European Way. There must be neither linguistic, nor cultural isolation, but free relationships, free development. The Baltic Way is the way of negotiations, persuasions and proofs.”36 It was a proclamation of the confident determination of all three Baltic nations that their history, culture, political will, and hope for the future lay with Western Europe. Within weeks of the speech, his formula “the Baltic Way is the European Way” was endorsed publicly and internationally by the largest-ever hand-linking demonstration on August 23, 1989. No similar declaration of the democratic will of three nations had previously been witnessed in this form These peoples were clearly determined to rejoin democratic Europe as sovereign nations.

On the home front, Sąjūdis was fully engaged in encouraging the Communist Party in Lithuania to separate from the Soviet Communist Party. During the fourth session in April of the Sąjūdžio Seimas, the Sąjūdis Parliament, a resolution was passed inviting the Lithuanian Communist Party to call an extraordinary meeting and to adopt a party program independent from Moscow. When this advice was accepted, it became evident that the fact that membership in the party had suddenly begun to drop sharply was among the reasons for the split from Moscow. Its leadership had finally realized that independence from Moscow could not be avoided if it was to retain its influence in Lithuania. That the decision was taken in defiance of warnings from Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviet Politburo became evident when Lithuanian reporters acquired the text of an unpublished resolution of the Soviet Politburo that accused the Lithuanian Communist Party and its First Secretary Algirdas Brazauskas of allowing “hesitations, inconsistencies and deviations from the resolutions of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.” It went on to declare that the Lithuanian Communist Party must “fulfill without delay” the CPSU policy “against federalization of the party and for preserving the party as one united whole.”37

Moscow followed this up by dispatching its chief ideologist, Politburo member Vadim A. Medvedev, to Lithuania. According to TASS, he warned the Lithuanian Communist Party on November 30 that their independence move was actively harming Gorbachev’s perestroika. Moscow’s television then publicized Medvedev’s statement that self-determination and secession were two different things. His plea was followed by an appeal from Gorbachev himself, published in the pages of the Lithuanian communist newspaper Tiesa (Truth) in which he wrote that the “common house of Europe” can only be built on the foundation of the acceptance of the realities of European politics. The article asserted that Soviet society and the Soviet state had become a “single organism” long ago. He also said, exposing a fundamental assumption, that the peaceful coexistence of the USSR with the West and Europe was dependent on a continuing Soviet presence in Lithuania and the other Baltic States. The actual limits of his openness were neatly expressed by the concurrent and carefully coordinated attack on Lithuania by Moscow’s Central Television. Further confirmation that official communist control of the media was “alive and well” came within days, when the rather open television program Vzglyad (View) was suddenly withdrawn from the Soviet television program schedule.

Despite these threats from the Kremlin, the Supreme Soviet of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic voted to strip the Communist Party of its leading role in society on December 7, 1989. This decision had already been taken in most Central European countries, but occupied Lithuania was the first republic in the Soviet Union to legalize alternative political parties. It was a historic decision of great significance, and the first of the newly registered parties was the 2,000-member Lietuvos demokratų partija, the Lithuanian Democratic Party, which advocated full independence as its central principle. This push for the legalization of a multiparty system was a further factor that helped orient Lithuania’s Communist Party toward its break with the Soviet party, and the Lithuanian precedent-setting action encouraged other republics to follow. The issue was discussed in the USSR Supreme Soviet, but by then both the Estonian and Armenian Supreme Soviets had passed similar provisions and also embodied them in their national constitutions. These changes were now moving very quickly with a self-confirming momentum. At the extraordinary meeting of the Lithuanian Communist Party held on December 19-20, 1989, 855 delegates voted in favor of complete separation from the Kremlin, in contrast to 160 delegates who were for autonomy within a reformed Soviet party. Twelve abstained. Following the vote, Vytautas Stakvilevičius, a member of both the Lithuanian Communist Party and Sąjūdis, stated that the Lithuanian nation wants independence and statehood,” adding that “whether our party is independent or not will also decide whether Lithuania will be independent or not.”38

It was now clear to the leader of the Lithuanian Communist Party, Algirdas Brazauskas, that the party could retain its popularity only by supporting independence. Choosing his words carefully and perhaps reserving a certain ambivalence on the matter, he observed that although Lithuania’s experience with independence was brief, it left a deep mark in people’s consciousness, adding that the restoration of Lithuanian statehood was the top priority of the party. “We are in favor of a sovereign Lithuanian state,” he said. “Sovereignty means political independence and the independence of the state in its domestic and foreign policy.”39 It is clear from these formulations that Sąjūdis’s stance had now entered the Realpolitik of even the most senior echelon of the Communist Party in occupied Lithuania. Speaking before the vote of December 20, Raimundas Kašauskas, a writer who was also a member of both the party and Sąjūdis, reminded the conference what Gorbachev had said when describing the changes in Eastern Europe: “Every nation has the right to choose its own way to develop its social structure.” Kašauskas then emphasized that the expression “all European nations includes us,” and added: “We are not less than anyone else in Eastern Europe.” It was this sentiment that carried the day, but it had consequences. Gorbachev’s reaction was furious. He responded by calling a two-day emergency meeting of the Soviet Communist Party on December 25-26, 1989, and Algirdas Brazauskas was heavily pressed during this meeting. However, his explanation of his position was honest:

I am not a grand master in politics, but I must stress that the main reason for what we’ve done was the desire to strengthen our position in the republic as a political force. That should be remembered in further actions, when we start talking about the structural changes in the party. Our main aim should be to preserve the leading role of the party. And I am heading towards that aim. … The Federation of Soviet Republics and the relations between the republics will not be static. They will change. The republics will be establishing new direct links with each other and with neighboring states.40

Brazauskas’s declaration was not received lightly. Yegor Ligachev, a hard-line member of the Politburo, commented later:

Even before the plenum and during the plenum, I was sure that we were dealing with people who had betrayed their fellow communists; I am talking about the Lithuanian Communist Party […] The former leaders of the Communist Party of Lithuania had broken the Party in half, and had created a break-away party that was designed to service Sąjūdis, the current leaders of Lithuania. That was sectarianism, pure and simple, and I said that at my speech at the plenum, and the time that has elapsed since has confirmed the truth of my words. They have defected to the other side, the other camp; they lost the influence they had had in Lithuania.41

Though they knew the strength of feeling against them and could feel the resentment, few Lithuanian political leaders expected Moscow to use force against Lithuania. Arvydas Juozaitis said publicly: “It is difficult to imagine, and I would say highly improbable, that while Gorbachev is talking about noninterference in Eastern Europe he would send tanks into Vilnius.”42 For the time being he was right because that reaction did not come until more than a year afterward, but the vote in Vilnius had left the first visible crack in the Soviet Communist Party since Lenin’s revolution. The Los Angeles Times commented that “the defection by one of the Soviet Union’s tinier republics seems to have rocked the Kremlin more than the collapse of communism in all six Warsaw Pact nations since August.”43

The wound was of course serious because it ran counter to the deepest delusions that were embodied in the world – the dominance expectations of Marxist ideology. The Communist Party that had held the Soviet Empire together since the Soviets abandoned Stalinist terror had expected to continue to do so. Gorbachev thus called the separation “illegitimate” and emphasized that “the current party and state leadership [in Moscow] will not permit the break-up of the state.”44 Eventually, in the hope of encouraging a reversal, the infuriated Kremlin Central Committee decided to send a 250-member delegation to Lithuania, as the Los Angeles Times humorously described it at the time, “to talk with virtually every one of the 200,000 members of the Lithuanian [Communist] party.”45 It was President Mikhail Gorbachev, who was also the CPSU General Secretary, who personally led this unprecedented explanatory mission to Lithuania. Landsbergis’s laconic response to the news was that Gorbachev would get a “warm reception in Lithuania” and would be greeted “as a leader of a friendly foreign state.”46 He was, as ever, the master of understatement.

On Christmas Eve, 1989, the deputies of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union finally adopted a resolution acknowledging that the Soviet-Nazi Pact of 1939 had violated the sovereignty and independence of the Baltic States. The statement also clarified the fact that the agreement then made was legally untenable and therefore invalid from the moment it was signed. That the resolution was passed in this form was due to a great extent to the influence and hard work of deputies from the Baltic States, particularly the Sąjūdis representatives. The underlying situation was now gathering momentum, as Latvia too was about to reject Communist Party supremacy. This was done a few days later on December 28, after a stormy debate in Riga’s Parliament, when members voted 220 to 50 to eliminate a section of the constitution that declared the Communist Party to be the “leading and guiding force of Soviet society.” The Latvian vote was further evidence of the strongly flowing tide of freedom. On the same day in Vilnius, tens of thousands of Lithuanians rallied to support the Lithuanian communists’ stand against the Kremlin. This rally was widely reported, and even the Soviet television program Vremya (Time) showed scenes of the demonstration on Gediminas Square numbering more than 50,000, commenting that “thousands of people gathered to hear bold, uncompromising speeches” supporting party independence.47 Gorbachev responded to these events by angrily denouncing the Lithuanian Communist Party and the movement for independence in one breath, but his speech also revealed that some of his own Central Committee members felt the Lithuanian Communist Party decision must be recognized as a fait accompli and that the Soviet party should give a political assessment only. This made it clear that the reform process had actually reached the politicians at this level, but he then went on to make it ominously plain that the majority had nevertheless argued in favor of strong measures to preserve the integrity of the party and state.

Gorbachev now unleashed a bitter attack against Sąjūdis, accusing it of “inflaming national sentiments” and “fomenting separatism” by attempting to “internationalize the so-called Baltic question.” This accusation implied the accompanying threat that the Soviet government would not permit the breakup of the Soviet Union. The speech was followed up by his three-day visit to Lithuania, which only served to strengthen support for the Lithuanian drive for independence. When he arrived, he met people in the squares and in the streets, but “the people very simply told him that they didn’t want to be within the Soviet Union.”48 Landsbergis recalled an episode in Šiauliai, “when he was talking to a worker, Gorbachev was using empty phrases, and as the phrases were having no result, he just went away and gave up.”49 He added that “in fact, it was his defeat in Lithuania, and perhaps the first such defeat in his trips to foreign countries.”50 Ligachev remembered in the BBC documentary “The Second Russian Revolution,” that he had talked with Gorbachev before his trip to Lithuania and afterward:

I insisted on my very clear views, and at some point I began to feel that we would not be able to save the situation by simple talk, by simple advice and recommendations. I felt that Brazauskas and I held different positions. Brazauskas was holding social democratic positions, whereas we were true communists. [...] It became quite clear to me at some point in that talk that recommendations and advice would not help, that we had to honestly and clearly say to our Party and to the Communist Party of Lithuania what was happening, and what was happening was a disintegration of our Party from within. Incidentally, [...] I mentioned to Gorbachev that what began to happen in Lithuania was a drive towards the secession of Lithuania from the Soviet Union. The process began within the Party: first they destroyed and split the Party, and then they tried to get out of the Soviet Union. Why? Because the Party had been the only force that could bring people together, organise people, it was this cohesive force that held people together. They wanted to remove that political force, by dividing it, by splitting it.51

Both during and after his work,

Gorbachev warned that the cost of

secession would be high and that the Lithuanian republic would have to

pay Moscow 33 billion dollars in compensation for Soviet investment.52

His blackmailing threats did not, however, pass without being parried.

Julius Juzeliūnas retorted:

I think this remark by Gorbachev is child’s talk, it is not serious … If they can present us with a bill, we can give them a bill, too. What about the 350,000 Lithuanians deported by Stalin to Siberia, half of whom died in exile or deportation? What about the industries here that produce only for Moscow and leave us only the pollution? We are one hundred percent colonized. These bills from Gorbachev are not serious; they would be modest compared to the bills we would present to Moscow.53

His response clearly voiced the prevailing public opinion in Lithuania at this point, and it is not surprising that only a few weeks later Sąjūdis won an overwhelming majority of seats in the Supreme Soviet of occupied Lithuania in the first multiparty election, which was held on February 24, and a “run-off” on March 4, 1990. This election presaged a major breakthrough in the process of reclaiming national independence, and on March 11, 1990, Sąjūdis’s Chairman, Vytautas Landsbergis, was elected President of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania, which was later called the Atkūriamasis Seimas, or Founding Parliament, by a vote of 91 to Brazauskas’s 38 votes. The legislature was now expected to steer the republic through the independence process. It was originally supposed to convene later in the month, but Sąjūdis’s leaders urgently decided to move the opening session forward because they had learned that a special meeting of the USSR Supreme Soviet had been called for March 12. Not unrealistically, they feared that the Supreme Soviet in the Kremlin would pass laws restricting the rights of republics to withdraw from the Soviet Union, which could seriously interfere with the drive for Lithuania’s secession unless Lithuanian independence had been declared beforehand. The Sąjūdis legislator Vladas Terleckas said that “we must not miss the moment for action, and this is our chance.”54 The crucial importance of the timing of the Declaration of Independence as a factor in Lithuania’s success has also been confirmed by President Vytautas Landsbergis, who presided over the fateful session of the nation’s Supreme Council, when the Lithuanian Parliament declared the restoration of Lithuania’s independence by 124 votes and 6 abstentions.

* * *

The Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania, expressing the will of the nation, resolves and solemnly proclaims that the execution of the sovereign power of the Lithuanian state, heretofore constrained by alien forces in 1940, is restored, and henceforth Lithuania is once again an independent state.

The February 16, 1918 Act of Independence of the Supreme Council of Lithuania and the May 15, 1920 Constituent Assembly Resolution on the restoration of a democratic Lithuanian state have never lost their legal force and are the constitutional foundation of the Lithuanian state.

The territory of Lithuania is integral and indivisible, and the constitution of any other state has no jurisdiction within it.

The Lithuanian state emphasises its adherence to universally recognised principles of international law, recognises the principles of the inviolability of borders as formulated in Helsinki in 1975 in the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, and guarantees the rights of individuals, citizens and ethnic communities.

The Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania, expressing sovereign power, by this act begins to achieve the state’s full sovereignty.55

WORKS CITED

Batūra, Romas. Baltijos

kelias – kelias į laisvę. 1989.08.23. Dešimtmetį minint.

Vilnius: Lietuvos Sąjūdis, 1999.

Genzelis, Bronius. Sąjūdis. Priešistorė ir istorija. Vilnius: Pradai, 1999.

Krickus, Richard. Showdown. The Lithuanian Rebellion and the Breakup of the Soviet Empire. Washington and London: Brassey’s, 1997.

Landsbergis, Vytautas. Lithuania Independent Again (Autobiography). Cardiff or Seattle: University of Wales Press or University of Washington Press, 2000.

Vardys, Vytautas S. “Sąjūdis: National Revolution in Lithuania.” In Jan A. Trapans (ed.) Toward Independence: the Baltic Popular Movements. Oxford: Westview Press, 1991.

Yakovlev, Alexander. The October Revolution and Perestroika. Moscow: Novosti Press Agency Publishing House, 1989.

|

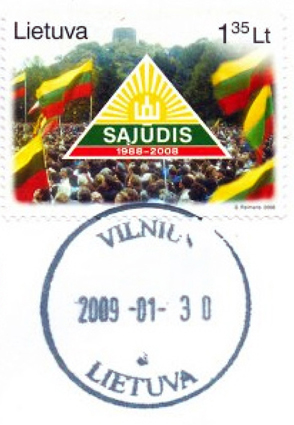

| Commemorative postage stamp of Sąjūdis’s 20th anniversary |